The Greek Crisis – Politics-Economics-Ethics

Listen here to the debate at the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, held on May 5th.

Listen here to the debate at the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, held on May 5th.

Speakers:

• Stathis Kouvelakis, Kings College, London

• Kevin Featherstone, Director, Hellenic Observatory, LSE

• Costas Lapavitsas, Economics, SOAS

• Peter Bratsis, Politics, Salford University

• Costas Douzinas (Chair) Birkbeck

Introduction by speakers:

Open debate:

Beg, Borrow or Steal: the Greek Crisis

by Alexandros Stavrakas

by Alexandros Stavrakas

The commentary on the Greek crisis has predictably descended into a spectacle of cheap moralisation. Over the past months, we have been bombarded with accusatory tirades aimed against corrupt politicians, greedy bankers, depraved technocrats and more or less anyone who’s had a chance to use and abuse the system in order to advance their personal interests or those of their clique.

Short-sightedness, lack of elementary moral constraints, blatant lying, sheer gluttony, political and financial opportunism, imaginative accountancy, cover-ups; all these, we have been tirelessly told, have resulted in the incontrovertible economical, political and moral downfall of Greece. Downfall is, of course, used loosely here, for it is hard to articulate whence Greece fell. It is, indeed, mind-bogglingly difficult for any person of my generation to try and find a precise point in the past thirty years when the financial and political scene in Greece was, to say the least, in order. Surely, there have been periods of relative prosperity, inflated as the latter could have only been (and this is not only known in retrospect, at least amongst somewhat informed people) – but to act surprised at the present situation can only be one of two things: naïve or fraudulent. Naïve for thinking that the party could go on forever; fraudulent for deliberately advertising this belief.

The Greek Crisis – Politics-Economics-Ethics

A debate to be held at the Birkbeck Institute of Humanities on May 5th, Wednesday 5th May 6.30pm – Room B04, 43 Gordon Sq.

Speakers:

Constantinos Tsoukalas, Emeritus Professor, University of Athens

Kevin Featherstone, Director – Hellenic Observatory, LSE

Costas Lapavitsas, Professor of Economics, SOAS

Costas Douzinas, Birkbeck

Peter Bratsis, Salford University

Jacqueline Rose on the Dreyfus Affair

Jacqueline Rose’s talk at the Asia Society on April 21 – organised by the London Review of Books on their 30th anniversary. Rose discusses parallels of the Affair with today’s political predicaments, including the role of the public intellectual.

Jacqueline Rose’s talk at the Asia Society on April 21 – organised by the London Review of Books on their 30th anniversary. Rose discusses parallels of the Affair with today’s political predicaments, including the role of the public intellectual.

If the player doesn’t work, click the link below:

Obama’s War

A talk by Tariq Ali in New York on Monday April 19th – organised by the London Review of Books

A talk by Tariq Ali in New York on Monday April 19th – organised by the London Review of Books

If the player doesn’t work, click below:

The End of Politics (2): Europe

by Costas Douzinas

How different does Europe look today from ten years ago. In 2000, influential commentators hailed the dawn of the ‘new European century’ to replace the atrocious ‘American’ 20th century. Europe was on the way to becoming the model polity for the new world. The re-unification of Germany, the successful introduction of the Euro and the expansion eastwards were ushering a new age of prosperity and freedom.

Read more…

The end of politics and the defence of democracy

by Costas Douzinas

In this month of the ‘Greek passion’ one thing is certain. The country will never be the same again. But while the commentators, academics and ‘experts’ discuss endlessly the economic crisis, the deep political malaise has gone unnoticed. The three ‘waves’ of ‘stability’ measures have befallen Greece like an evil tsunami which will turn the current recession into a depression with no clear end. But they also attack the foundations of democracy. The unfolding events offer a panorama of the symptoms of ‘the end of politics’. Read more…

Thatcher, Thatcher, Thatcher

by John Gray

from the London Review of Books

There wasn’t anything inevitable about David Cameron’s rise. If Kenneth Clarke had stirred himself into running something like a campaign when competing for the leadership with Iain Duncan Smith and been ready to appear more tractable on Europe; if David Davis had moved decisively in the immediate aftermath of Michael Howard’s resignation or been a more fluent speaker; if Howard had offered Cameron the shadow chancellorship or George Osborne had not accepted it – if these or any number of other contingencies had been otherwise, Cameron might not have become leader. Yet he has been perceived as an unstoppable force, the author of an irreversible transformation in his party that has set it firmly back on the road to power. Tim Bale’s exhaustive and authoritative account is hedged throughout with academic caution, but it concludes in terms that treat the Conservatives’ return to office as a foregone conclusion: ‘just as was the case for Margaret Thatcher, Cameron will ultimately be judged and defined by what he does.’ more

Why Google is the Nike of the internet

by Alexandros Stavrakas

from The Guardian

Google decided two weeks ago to shut down its hitherto self-censoring search service in China. This allegedly costly gesture, intended as a bold statement rather than a formal articulation of corporate “foreign policy”, is congruous with the company’s liberal philosophy and juxtaposed to the aged conformity of, say, Microsoft. But far from being seen merely as an act of adolescent bravado or tedious corporate management, it seems to have captured the imagination of intellectuals around the world. more

Google decided two weeks ago to shut down its hitherto self-censoring search service in China. This allegedly costly gesture, intended as a bold statement rather than a formal articulation of corporate “foreign policy”, is congruous with the company’s liberal philosophy and juxtaposed to the aged conformity of, say, Microsoft. But far from being seen merely as an act of adolescent bravado or tedious corporate management, it seems to have captured the imagination of intellectuals around the world. more

Peter Hallward on “Damming the Flood: Haiti, Aristide, and the Politics of Containment”

from Democracy Now

Haitian President Rene Preval said Sunday that the death toll from the earthquake could reach 300,000 once all the bodies are recovered from the rubble. We speak to Peter Hallward, professor of Modern European Philosophy at Middlesex University. “Unless prevented by renewed popular mobilisation in both Haiti and beyond, the perverse international emphasis on security will continue to distort the reconstruction effort, and with it the configuration of Haitian politics for some time to come,” wrote Hallward recently. “What is already certain is that if further militarisation proceeds unchecked, the victims of the January earthquake won’t be the only avoidable casualties of 2010.”

Badiou/Zizek: Philosophy in the Present

To mark our comeback, after a long period of inactivity, here’s a copy of Philosophy in the Present by Alain Badiou & Slavoj Zizek.

Our role in Haiti’s plight

by Peter Hallward

from The Guardian

Any large city in the world would have suffered extensive damage from an earthquake on the scale of the one that ravaged Haiti’s capital city on Tuesday afternoon, but it’s no accident that so much of Port-au-Prince now looks like a war zone. Much of the devastation wreaked by this latest and most calamitous disaster to befall Haiti is best understood as another thoroughly manmade outcome of a long and ugly historical sequence.

The country has faced more than its fair share of catastrophes. Hundreds died in Port-au-Prince in an earthquake back in June 1770, and the huge earthquake of 7 May 1842 may have killed 10,000 in the northern city of Cap Haitien alone. Hurricanes batter the island on a regular basis, mostly recently in 2004 and again in 2008; the storms of September 2008 flooded the town of Gonaïves and swept away much of its flimsy infrastructure, killing more than a thousand people and destroying many thousands of homes. The full scale of the destruction resulting from this earthquake may not become clear for several weeks. Even minimal repairs will take years to complete, and the long-term impact is incalculable.

What is already all too clear, however, is the fact that this impact will be the result of an even longer-term history of deliberate impoverishment and disempowerment. Haiti is routinely described as the “poorest country in the western hemisphere”. This poverty is the direct legacy of perhaps the most brutal system of colonial exploitation in world history, compounded by decades of systematic postcolonial oppression. more

Slavoj Žižek – Living in the End Times

Inhuman Thoughts // by Asher Seidel

Inhuman Thoughts is a philosophical exploration of the possibility of increasing the physiological and psychological capacities of humans to the point that they are no longer biologically, psychologically, or socially human. The movement is from the human through the trans-human, to the post-human. The tone is optimistic; Seidel argues that such an evolution would be of positive value on the whole.

Inhuman Thoughts is a philosophical exploration of the possibility of increasing the physiological and psychological capacities of humans to the point that they are no longer biologically, psychologically, or socially human. The movement is from the human through the trans-human, to the post-human. The tone is optimistic; Seidel argues that such an evolution would be of positive value on the whole.

Seidel’s initial argument supports the need for a comprehensive ethical theory, the success of which would parallel that of a large-scale scientific revolution, such as Newtonian mechanics. He elaborates the movement from the improved-but-still-human to the post-human, and philosophically examines speculated examples of post-human forms of life, including indefinitely extended life-span, parallel consciousness, altered perception, a-sociality, and a-sexuality.

Inhuman Thoughts is directed at those interested in philosophical questions on human nature and the best life given the possibilities of that nature. Seidel’s overall argument is that the most satisfactory answer to the latter question involves a transcendence of the present confines of human nature.

Rebuilding Afghanistan

by Tariq Ali

from the London Review of Books blog

P.J.Tobia’s photographs of these monstrous buildings in Kabul convey only part of the horror. Their location is not too far from the slum dwellings that house the poor of the city, sans water, sans electricity, sans sewage, sans everything. A young photo-journalist from Philadelphia, Tobia supplied the captions and writes on True/Slant:

P.J.Tobia’s photographs of these monstrous buildings in Kabul convey only part of the horror. Their location is not too far from the slum dwellings that house the poor of the city, sans water, sans electricity, sans sewage, sans everything. A young photo-journalist from Philadelphia, Tobia supplied the captions and writes on True/Slant:

Here in Kabul, the poor live in unimaginably squalid conditions and the rich live like kings. Kings in very ugly castles.

We call them Poppy Palaces or Narcotecture, because much of the money that went into building them came from Afghanistan’s biggest crop. I also suspect that some UN/NGO/USAID dollars are paying for these insults to taste and design.

You can see these monstrosities all over town and I’ve photographed a few of the worst for your viewing pleasure. Note the really high walls and metal armor on some of them.

I apologize for the hurried nature of these photos—I took most of them from a moving car—but the AK-47 toting guards who stand watch at these palaces become a bit, um, grumpy when you take pictures around them.

Nice to actually see what Euro-American soldiers are killing and dying for. more

The Courtesy of God

by Garret Keizer

from Lapham’s Quarterly

The devil you say

These days what the Epistle of James says about believing in God—that the devils believe in him too, ergo beware of taking too much credit for your credos—is often on my mind. God may or may not be in his heaven, but on any given week he is likely to be enthroned at the top of that great chain of being known as the New York Times Best Sellers List. Like James and the devil, I am not impressed.

By that I do not mean that I consider myself beyond the God debate or beyond those of my fellow mortals who find it compelling. In fact, if there is any unifying notion in what you are about to read, it is my deep distrust of any human being who fancies himself “beyond” just about anything, be it money, jealousy (of best-selling authors, for instance), using a turn signal, or putting on a tie. I would never buy a book whose title began with Beyond, though I have known a few beyond-good-and-evil types who weren’t beyond stealing one.

If I am unimpressed with the God debate it is less for wanting to seem aloof than for needing to start with easier questions. Lacking the credentials, say, that entitle any expert on a nanolayer of slime covering a pebble called earth to give us the complete skinny on absolute being, a hubris beside which the nitwit ruling of a Kansas school board seems cautiously understated, I want questions better suited to my pay grade. Never mind does God exist—does the God debate exist? more

Toward a Theory of Surprise

by Chris Bachelder

from Believer

Three mornings a week I drop off my three-and-a-half-year-old daughter at her daycare center. We have a routine. First we read a book, then we hug, kiss, high five, and wave before I leave. That’s how every drop-off goes. One recent morning she squirmed throughout the book, distractedly performed our separation ritual, then stopped me from departing by grabbing my wrist. She leaned sideways at the waist and with her other hand gripped the back of her knee. “Dad,” she said, “there’s something weird in my leggings.”

Three mornings a week I drop off my three-and-a-half-year-old daughter at her daycare center. We have a routine. First we read a book, then we hug, kiss, high five, and wave before I leave. That’s how every drop-off goes. One recent morning she squirmed throughout the book, distractedly performed our separation ritual, then stopped me from departing by grabbing my wrist. She leaned sideways at the waist and with her other hand gripped the back of her knee. “Dad,” she said, “there’s something weird in my leggings.”

I turned her around and felt the back of her leg with the tips of my fingers. Sure enough, there was something weird in her leggings. The weird something was small and hard, seemingly unattached to her skin. It felt like a stone, a piece of gravel. In half a life how many rocks have I pulled from my socks? The adult mind settles quickly.

“What is it, Dad?” my daughter asked.

“I think it’s a rock,” I said. more

The Pictures of War You Aren’t Supposed to See

By Chris Hedges

from truthdig.com

War is brutal and impersonal. It mocks the fantasy of individual heroism and the absurdity of utopian goals like democracy. In an instant, industrial warfare can kill dozens, even hundreds of people, who never see their attackers. The power of these industrial weapons is indiscriminate and staggering. They can take down apartment blocks in seconds, burying and crushing everyone inside. They can demolish villages and send tanks, planes and ships up in fiery blasts. The wounds, for those who survive, result in terrible burns, blindness, amputation and lifelong pain and trauma. No one returns the same from such warfare. And once these weapons are employed all talk of human rights is a farce.

War is brutal and impersonal. It mocks the fantasy of individual heroism and the absurdity of utopian goals like democracy. In an instant, industrial warfare can kill dozens, even hundreds of people, who never see their attackers. The power of these industrial weapons is indiscriminate and staggering. They can take down apartment blocks in seconds, burying and crushing everyone inside. They can demolish villages and send tanks, planes and ships up in fiery blasts. The wounds, for those who survive, result in terrible burns, blindness, amputation and lifelong pain and trauma. No one returns the same from such warfare. And once these weapons are employed all talk of human rights is a farce.

In Peter van Agtmael’s “2nd Tour Hope I don’t Die” and Lori Grinker’s “Afterwar: Veterans From a World in Conflict,” two haunting books of war photographs, we see pictures of war which are almost always hidden from public view. These pictures are shadows, for only those who go to and suffer from war can fully confront the visceral horror of it, but they are at least an attempt to unmask war’s savagery. more

‘First they called me a joker, now I am a dangerous thinker’ // Slavoj Zizek talks to The Times of India

Slavoj Zizek is an unusual philosopher with unfashionably inflexible left-wing views. He also loves Hollywood classics. The 59-year-old academic has written more than 30 books on subjects as diverse as Alfred Hitchcock, Lenin and 9/11. A self-proclaimed Leninist, the Slovenian thinker believes that “communism will triumph finally”. On his first visit to India this week, Zizek spoke about global capitalism, Gandhi, Bollywood and Buddhism. Excerpts from the interview:

You call yourself a Leninist but the media in the West has called you a ‘rock star’ and the ‘Marx Brother’. How do you react to such labels?

With resigned melancholy. They try to say that this guy may be interesting and provocative but he is not serious. To them, I am like a fly that annoys you and provokes you but should not be taken seriously. Though, of late, they have been dubbing me as someone more threatening. In the last two years, the tone has changed. First, there were Marx Brothers’ jokes and now they say I am the most dangerous philosopher in the West. But I don’t care.

You also don’t care when they say that you glorify political violence.

For me, the 20th century communism is the biggest ethical-political catastrophe in history, greater catastrophe than fascism. But in the first years of the October Revolution, in spite of the so-called Red Terror, there was sexual liberation and literary explosion before it turned into a nightmare. I don’t accept the right-wing critique that says it was evil from the very beginning.

Read more of this insignificant interview here

Untitled Video on Lynne Stewart and Her Conviction, The Law, and Poetry (2006) // by Paul Chan

On February 10, 2005, Lynne Stewart was convicted of providing material support for a terrorist conspiracy. She is the first lawyer to be convicted of aiding terrorism in the United States. Stewart faces thirty years of prison and will be sentenced in September 2006.

Untitled… is a video portrait of Stewart. The video focuses on the relationship between the language of poetry and the language of the law. Stewart speaks both languages, and employs poetry as a “knotting point” to connect ideas of beauty and justice for juries and judges alike. The film takes Stewart’s understanding of poetry and the law as a departure point to explore the possibilities of a poetics capable of articulating the pressures of terror and justice.

“Paul Chan’s portrait [is] of Lynne F. Stewart, the New York lawyer convicted last year of aiding Islamic terrorism by smuggling messages out of jail from a client she was defending, Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman. Now disbarred, Ms. Stewart faces a 30-year jail sentence.

The film, which Mr. Chan calls a work-in-progress, simply shows Ms Stewart talking; in a sense it is a self-portrait. She talks about her trial, about her career as an activist lawyer and about a personal politics that sounds instinctual rather than ideological. She also read poetry.

One of the poems she reads is William Blake’s “On Another’s Sorrow” from “Songs of Innocence”. It isn’t “political” in any overt way. It is filled with both questions and answers. While she reads, Mr. Chan turns the screen into a field of changing colors, so that we concentrate on the music of the words, the activism of the soul that poetry is, the power outlet that art can be. It’s a simple device, and like any effective political action, right or wrong, brilliant because it works.” –Holland-Cotter, New York Times, January 17th 2006

In the next decade, I hope to become more radical

by Costas Douzinas

from The Guardian

How different things looked in 1900 and 2000. The end of the 19th century was drowned in fin de siècle gloom. The end of the 20th century was, on the contrary, exuberant. President Bush Sr triumphantly announced in 1991 that a “new world order” was coming into view in which “the principles of justice and fair play will protect the weak against the strong [and] freedom and humanity will find a home among nations … Enduring peace must be our mission.” As the world was entering a new century of supposed peace and prosperity, I was hitting my half-century, a point of some pride and much foreboding. Melancholic retrospection and hopeful planning was the order of the day – for the world and me.

Globalisation, neoliberal economics and humanitarian cosmopolitanism were the contours of the new age. Economic interdependence, global communications, free trade, population and capital flows were bringing the world together, undermining the omnipotence of sovereignty and nation-state. A global civil society of multinational corporations, as well as international and non-governmental organisations, were to create the transnational solidarities necessary to protect against global risks. more

Evangelicalism and the Contemporary Intellectual

A panel discussion with Malcolm Gladwell, Christine Smallwood, and James Wood, moderated by Caleb Crain.

Watch here.

The Darwin Show

by Steven Shapin

from The London Review of Books

It has been history’s biggest birthday party. On or around 12 February 2009 alone – the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth, ‘Darwin Day’ – there were more than 750 commemorative events in at least 45 countries, and, on or around 24 November, there was another spate of celebrations to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or, the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. In Mysore, Darwin Day was observed by an exhibition ‘proclaiming the importance of the day and the greatness of the scientist’. In Charlotte, North Carolina, there were performances of a one-man musical, Charles Darwin: Live & in Concert (‘Twas adaptive radiation that produced the mighty whale;/His hands have grown to flippers/And he has a fishy tail’). At Harvard, the celebrations included ‘free drinks, science-themed rock bands, cake, decor and a dancing gorilla’ (stuffed with a relay of biology students). Circulating around the university, student and faculty volunteers declaimed the entire text of the Origin.

On the Galapagos Islands, tourists making scientific haj were treated to ‘an active, life-seeing account of the life of this magnificent scientist’, and a party of Stanford alumni retraced the circumnavigating voyage of HMS Beagle in a well-appointed private Boeing 757, intellectually chaperoned by Darwin’s most distinguished academic biographer. The Darwin anniversaries were celebrated round the world: in Bogotá, Mexico City, Montevideo, Toronto, Toulouse, Frankfurt, Barcelona, Bangalore, Singapore, Seoul, Osaka, Cape Town, Rome (where it was sponsored by the Pontifical Council for Culture, part of a Vatican hatchet-burying initiative), and in all the metropolitan and scientific settings you might expect. The English £10 note has borne Darwin’s picture on the back since 2000 (replacing Dickens), but special postage stamps and a new £2 coin honoured him in 2009, as did stamps or coins in at least ten other countries. more

Wanting to Be Something Else

by Adam Shatz

Who could resist the charms, or doubt the importance, of a liberal, secular, Turkish Muslim writing formally adventurous, learned novels about the passionate collision of East and West? Orhan Pamuk is frequently described as a bridge between two great civilisations, and his major theme – the persistence of memory and tradition in Westernising, secular Turkey – is of a topicality, a significance, that it seems churlish to deny. His eight novels, the most recent of which, The Museum of Innocence, has just appeared in English, perform formal variations on that theme. Though his work fits into a Turkish tradition most closely associated with the mid-20th-century novelist Ahmet Tanpinar, one needn’t know anything about Tanpinar, or even about Turkish literature, to appreciate Pamuk, who writes in the Esperanto of international literary fiction, employing a playful postmodernism that freely mixes genres, from detective fiction to historical romance. Much of Pamuk’s fiction reads like a homage to his Western models: Mann, Faulkner, Borges, Joyce, Dostoevsky, Proust and – in The Museum of Innocence, the tale of a doomed, obsessional love affair between a man in his thirties and an 18-year-old shop girl – Nabokov. Indeed, his affection for the European tradition is as crucial to his appeal as his Turkishness, and his books pay tribute to values deeply embedded in the liberal imagination: romantic love freed from the fetters of tradition; individual creativity; freedom and tolerance; respect for difference. more

Mandates of Heaven

by Lewis Lapham

from Lapham’s Quarterly

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly doesn’t trade in divine revelation, engage in theological dispute, or doubt the existence of God. What is of interest are the ways in which religious belief gives birth to historical event, makes law and prayer and politics, accounts for the death of an army or the life of a saint. Questions about the nature or substance of deity, whether it divides into three parts or seven, speaks Latin to the Romans, in tongues when traveling in Kentucky, I’ve learned over the last sixty-odd years to leave to sources more reliably informed. My grasp of metaphysics is as imperfect as my knowledge of Aramaic. I came to my early acquaintance with the Bible in company with my first readings of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Bulfinch’s Mythology, but as an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not.

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly doesn’t trade in divine revelation, engage in theological dispute, or doubt the existence of God. What is of interest are the ways in which religious belief gives birth to historical event, makes law and prayer and politics, accounts for the death of an army or the life of a saint. Questions about the nature or substance of deity, whether it divides into three parts or seven, speaks Latin to the Romans, in tongues when traveling in Kentucky, I’ve learned over the last sixty-odd years to leave to sources more reliably informed. My grasp of metaphysics is as imperfect as my knowledge of Aramaic. I came to my early acquaintance with the Bible in company with my first readings of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Bulfinch’s Mythology, but as an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not.

Four years at Yale College in the 1950s rendered the question moot. It wasn’t that I’d missed the explanation; there was no explanation to miss, at least not one accessible by means other than the proverbial leap of faith. Then as now, the college was heavily invested in the proceeds of the Protestant Reformation, the testimony of God’s will being done present in the stonework of Harkness Tower and the cautionary ringing of its bells, as well as in the readings from scripture in Battell Chapel and the petitionings of Providence prior to the Harvard game. The college had been established in 1701 to bring a great light unto the gentiles in the Connecticut wilderness, the mission still extant 250 years later in the assigned study of Jonathan Edwards’ sermons and John Donne’s verse. Nowhere in the texts did I see anything other than words on paper—very beautiful words but not the living presence to which they alluded in rhyme royal and iambic pentameter. I attributed the failure to the weakness of my imagination and my poor performance at both the pole vault and the long jump. more

Yes, It Was Torture, and Illegal

Editorial

from The New York Times

Bush administration officials came up with all kinds of ridiculously offensive rationalizations for torturing prisoners. It’s not torture if you don’t mean it to be. It’s not torture if you don’t nearly kill the victim. It’s not torture if the president says it’s not torture.

It was deeply distressing to watch the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit sink to that standard in April when it dismissed a civil case brought by four former Guantánamo detainees never charged with any offense. The court said former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and the senior military officers charged in the complaint could not be held responsible for violating the plaintiffs’ rights because at the time of their detention, between 2002 and 2004, it was not “clearly established” that torture was illegal. more

Uncovering Céline

by Wyatt Mason

from The New York Review of Books

1.

Louis-Ferdinand Destouches met Cillie Pam in Paris, at the Café de la Paix, in September 1932. Destouches was a physician who worked at a public clinic in Clichy treating poor and working-class patients; Pam was a twenty-seven-year-old Viennese gymnastics instructor eleven years his junior on a visit to the city. Destouches suggested a stroll in the Bois de Boulogne, took Pam to dinner later that night, and afterward took her home. Two weeks together began, after which Pam returned to her work and life in Vienna. Over the next seven years, they saw each other infrequently but corresponded regularly. Pam, who was Jewish, married and had a son. Destouches, who wrote in his free time, became famous shortly after their brief affair, his first novel, Voyage au bout de la nuit, published at the end of 1932 under the pseudonym “Céline” (his maternal grandmother’s first name), proving an enormous success. In February 1939, Destouches received word that Pam had lost her husband: he had been seized, sent to Dachau, and killed. On February 21, Destouches wrote to Pam, who had fled abroad:

Skepticism via YouTube

by Tim Farley

from CSI

Figure 1: The Center for Inquiry's YouTube Channel

In the summer of 2008, Georgians Matthew Whitton and Rick Dyer claimed to have found a Bigfoot carcass. These claims were initially made via a number of YouTube videos that garnered significant attention in the cryptid community. In August 2008, they partnered with well-known cryptozoology personality Tom Biscardi for a national press conference. Almost immediately the carcass was revealed as a hoax involving a Halloween costume.

But a month earlier, rival Bigfoot enthusiasts and skeptics had carefully pored over one of Whitton and Dyer’s promotional videos on YouTube (“Bigfoot Tracker Video 8”) in which they met an alleged Texas scientist named Paul Van Buren who said he would authenticate the carcass (Bigfootpolice 2008). Sharp-eyed viewers quickly determined that “Van Buren” was actually Whitton’s brother, a wedding photographer from Texas, and even found pictures online of the two together at one of their weddings (Coleman 2008). more

Night

by Tony Judt

from The New York Review of Books

I suffer from a motor neuron disorder, in my case a variant of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): Lou Gehrig’s disease. Motor neuron disorders are far from rare: Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and a variety of lesser diseases all come under that heading. What is distinctive about ALS—the least common of this family of neuro-muscular illnesses—is firstly that there is no loss of sensation (a mixed blessing) and secondly that there is no pain. In contrast to almost every other serious or deadly disease, one is thus left free to contemplate at leisure and in minimal discomfort the catastrophic progress of one’s own deterioration.

In effect, ALS constitutes progressive imprisonment without parole. First you lose the use of a digit or two; then a limb; then and almost inevitably, all four. The muscles of the torso decline into near torpor, a practical problem from the digestive point of view but also life-threatening, in that breathing becomes at first difficult and eventually impossible without external assistance in the form of a tube-and-pump apparatus. In the more extreme variants of the disease, associated with dysfunction of the upper motor neurons (the rest of the body is driven by the so-called lower motor neurons), swallowing, speaking, and even controlling the jaw and head become impossible. I do not (yet) suffer from this aspect of the disease, or else I could not dictate this text. more

Speak No Evil

by John B. Judis

from The New Republic

The lines most cited in Barack Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize speech were those about evil: “Evil does exist in the world. A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies. Negotiations cannot convince Al Qaeda’s leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism–it is a recognition of history, the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.”

The lines most cited in Barack Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize speech were those about evil: “Evil does exist in the world. A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies. Negotiations cannot convince Al Qaeda’s leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism–it is a recognition of history, the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.”

These lines won approbation from both liberals and conservatives. Former Clinton aide Bill Galston praised them as an example of Obama’s “moral realism.” According to neoconservative Bob Kagan, Obama didn’t “shy away from the Manichaean distinctions that drive self-described realists (and Europeans) crazy.” Former Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson said the lines marked the speech as “very American.” “He didn’t speak as kind of the citizen of the world, as sometimes he has in the past,” Gerson added approvingly. more

The Soviet Victory That Never Was

by Nikolas K. Gvosdev

from Foreign Affairs

Could the Soviet Union have won its war in Afghanistan? Today, the victory of the anti-Soviet mujahideen seems preordained as part of the West’s ultimate triumph in the Cold War. To suggest that an alternative outcome was possible — and that the United States has something to learn from the Soviet Union’s experience in Afghanistan — may be controversial. But to avoid being similarly frustrated by the infamous “graveyard of empires,” U.S. military planners would be wise to study how the Soviet Union nearly emerged triumphant from its decade-long war.

There are, of course, some fundamental differences between the Soviets’ war in the 1980s and the U.S.-led mission today. First, the Soviet Union intervened to save a communist regime which was in danger of collapsing due to resistance to its comprehensive and often traumatic social-engineering programs. Unlike the Soviets and their client regime, the United States is not interested in forcibly removing the burkas from Afghan women, shooting large numbers of mullahs for resisting secularization, or reprogramming the political and social mores of Afghans. Instead, Washington has a far more limited objective: namely, ensuring that Afghanistan remains an inhospitable base for extremist groups hoping to attack the West. more

Six Questions for John Scott-Railton on Cambodia

by Ken Silverstein

from Harper’s Magazine

While completing a master’s degree at the University of Michigan, John Scott-Railton helped develop “participatory mapping” projects aimed at protecting the fragile property rights of poor families living in Phnom Penh. While there he became an advocate of transparency in Cambodia’s natural resource management. Scott-Railton, now a doctoral student at the University of California-Los Angeles, has traveled extensively in Cambodia and throughout Southeast Asia. I recently asked him six questions about the political situation in Cambodia and the role there of the international community. (Note: For a look at the apparel industry in Cambodia, which is promoted by industry as the “anti-sweatshop country,” see my piece in the January issue of Harper’s.)

1. In theory, Cambodia has emerged as a multiparty democracy with political freedoms. What’s the general state of democracy in Cambodia? more

Missing the Point

by Colm Tóibín

from The London Review of Books

From an early age, I have missed the point of things. I noticed this first when the entire class at school seemed to understand that Animal Farm was about something other than animals. I alone sat there believing otherwise. I simply couldn’t see who or what the book was about if not about farm animals. I had enjoyed it for that. Now, the teacher and every other boy seemed to think it was really about Stalin or Communism or something. I looked at it again, but I still couldn’t quite work it out.

From an early age, I have missed the point of things. I noticed this first when the entire class at school seemed to understand that Animal Farm was about something other than animals. I alone sat there believing otherwise. I simply couldn’t see who or what the book was about if not about farm animals. I had enjoyed it for that. Now, the teacher and every other boy seemed to think it was really about Stalin or Communism or something. I looked at it again, but I still couldn’t quite work it out.

So, too, with a lot of poetry. I couldn’t see that things were like other things when they were not like them. Maybe they were slightly like them, or somewhat like them, but usually they were not like them at all.

And allegory. I never got the point of allegory. If it was a choice between algebra and allegory, I knew whose side I was on. When I picked up Moby Dick, I liked it because it was about hunting whales. And oh dear I just couldn’t concentrate when everyone began to explain, all at the one time, that the whale was a symbol or something, that it stood for… I cannot remember what. more

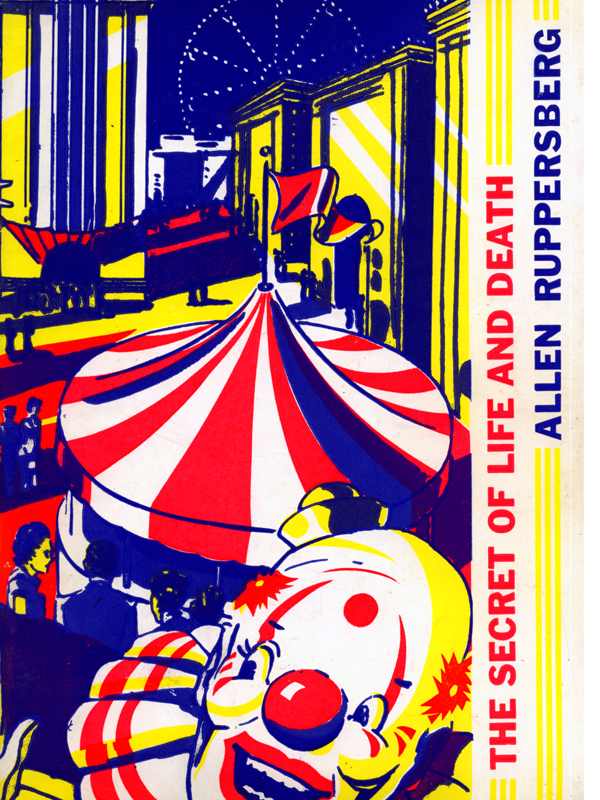

Allen Ruppersberg for Bedeutung Magazine: The Secret of Life and Death

Postscript: Paul Samuelson

by John Cassidy

from The New Yorker

In the fall of 1996, I arranged to interview Paul Samuelson in his office at M.I.T. for an article I was writing on the state of economics, which is available online to subscribers. At the allotted time, 12:00 if I remember rightly, there was no sign of Samuelson, who was then eighty-one. A few minutes went by. Then he bounced in on the soles of his feet, a diminutive man dressed in a light gray suit, a red-and-white-striped shirt, and a snazzy bow tie. He had gray, frizzy hair, shaggy eyebrows, and a wicked smile. His usual parking space had been occupied, he shouted to his secretary, so he had been forced to park in somebody else’s. “I hope it’s Franco’s. He’s out of town.” (Franco was Franco Modigliani, a fellow M.I.T. Nobel Laureate, who died in 2003.)

Befitting a scholar of his stature, Samuelson had a big airy office that overlooked the Charles River. Books and journals lined the walls and floors, but Samuelson’s desk was neat. On the blackboard, there was a note of congratulations from his colleagues for winning the “National Medal of Science,” which he had received at the White House earlier that year. Samuelson joined M.I.T.’s faculty in 1940. He wrote more than four hundred journal articles, numerous monographs and a famous undergraduate textbook, which, he proudly informed me, had sold “three million or four million copies—I can’t remember which.” When he was awarded the Nobel Prize, in 1970, the citation read: “By his contributions, Samuelson has done more than any other contemporary economist to raise the level of scientific analysis in economic theory.” Almost forty years later, few would quibble with that description. more

Even Bigger Than Too Big to Fail

Editorial from The New York Times

Asserting that it “is among the strongest banks in the industry,” Citigroup announced on Monday that it would soon repay $20 billion of federal bailout money. This from a bank that has been in the red for most of the past two years, that is expected to limp through 2010 amid a torrent of loan losses, that saw its stock price close after the announcement at a measly $3.70 a share — and that, like other big banks, is still reluctant to lend.

Meanwhile, the Treasury Department, which seems to have no qualms about Citigroup’s self-proclaimed strength, plans to sell its $25 billion stake over the next six to 12 months.

Citigroup’s planned exit from the bailout — like Bank of America’s earlier this month — would be welcome if the banks were the picture of health. But their main motive is to get out from under the bailout’s pay caps and other restraints. The Treasury Department’s approval is a grim reminder of the political power of the banks, even as the economy they did so much to damage continues to struggle. more

On the Couch with Philip Roth, at the Morgue with Pol Pot

by Charles Simic

from The New York Review of Books blog

As a rule, I read and write poetry in bed; philosophy and serious essays sitting down at my desk; newspapers and magazines while I eat breakfast or lunch, and novels while lying on the couch. It’s toughest to find a good place to read history, since what one is reading usually is a story of injustices and atrocities and wherever one does that, be it in the garden on a fine summer day or riding a bus in a city, one feels embarrassed to be so lucky. Perhaps the waiting room in a city morgue is the only suitable place to read about Stalin and Pol Pot?

As a rule, I read and write poetry in bed; philosophy and serious essays sitting down at my desk; newspapers and magazines while I eat breakfast or lunch, and novels while lying on the couch. It’s toughest to find a good place to read history, since what one is reading usually is a story of injustices and atrocities and wherever one does that, be it in the garden on a fine summer day or riding a bus in a city, one feels embarrassed to be so lucky. Perhaps the waiting room in a city morgue is the only suitable place to read about Stalin and Pol Pot?

Oddly, the same is true of comedy. It’s not always easy to find the right spot and circumstances to allow oneself to laugh freely. I recall attracting attention years ago riding to work on the packed New York subway while reading Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 and bursting into guffaws every few minutes. One or two passengers smiled back at me while others appeared annoyed by my behavior. On the other hand, cackling in the dead of the night in an empty country house while reading a biography of W.C. Fields may be thought pretty strange behavior too. more

The Noughties: a fond(ish) farewell

by Toby Young

from the Telegraph

I was in a French ski resort on January 1 2000 and the first thing I thought about, when the fog of the previous night began to clear, was the Millennium Bug. Deputy US Defence Secretary John Hamre had predicted it would be ‘the electronic equivalent of the El Niño’.

I was in a French ski resort on January 1 2000 and the first thing I thought about, when the fog of the previous night began to clear, was the Millennium Bug. Deputy US Defence Secretary John Hamre had predicted it would be ‘the electronic equivalent of the El Niño’.

Just how many planes had fallen out of the sky at the stroke of midnight? I plugged my laptop into a phone socket and heard the sound that will forever be associated with the turn of the century: ‘Eeeeee, orrrrrrrrrrrr, ooo-a-ooo-a-ooo-a-ooo-a.’

There was a pause. Had I got through? No, I hadn’t.

‘Eeeeee, orrrrrrrrrrrr, ooo-a-ooo-a-ooo-a-ooo-a.’ Dear God, how I came to hate that sound.

When I discovered that absolutely nothing had happened I felt vaguely disappointed. On the face of it, that makes me sound like a depraved nihilist – I was upset that a global disaster hadn’t occurred – but it was a sickness shared by many and, though I didn’t know it at the time, symptomatic of the decade to come. more

I Could Fix That

by David Runciman

from The London Review of Books

In the final year of the last century, George Stephanopoulos, Bill Clinton’s one-time aide and press secretary, published a memoir of his time in the White House entitled All Too Human: A Political Education. Back then, it seemed like a terribly exciting book: 1999 was the year of Clinton’s Senate trial, following his impeachment, and also of the first appearance on US television of The West Wing, which offered the fantasy of a different kind of liberal president. Stephanopoulos made working in Clinton’s West Wing sound thrilling, monstrous, deranged. A group of super-smart men (and one or two women) fought round the clock to pin down their super-smart, hopelessly promiscuous president (promiscuous with his time, his interests, his attention, rather than in the more obvious ways). Speeches got written at the last moment, policy was endlessly being reformulated, old enemies were reached out to while a train of new enemies was picked up along the way. Stephanopoulos describes how important physical proximity to the president was – having your office a few yards nearer to the Oval Office than the next person was crucial – and he lets us know that he got close. This was more like a medieval court than a modern workplace, both deeply hierarchical and frighteningly chaotic. And there at the heart of it was George, fixing, fighting, cajoling, despairing, scheming, outwitting, getting outwitted, and all the time feeding off the power. At one point, our hero (George, not Bill) takes a fancy to Jennifer Grey, Patrick Swayze’s costar in Dirty Dancing, and he gets his people to sound out her people about whether she fancies a date. Yes she does! He goes to gatherings of Greek-Americans and they crowd round wanting to know when he is going to lift the curse of Dukakis (which says that short Greek men can’t get elected president, because they look ridiculous in tanks). What can George say – who knows? more

Greek debt crisis: Let’s not return to status quo

by Alexandros Stavrakas

from: The Guardian

If by “hope” we mean a feeling of yearning and expectation for something to happen, and by “change” we mean an improvement of our present condition, then this is Greece’s moment of hope and change – and it is an overdue moment indeed. But, before this moment is lost in indiscernible patterns of technocratic parlance, financial speculation and micro-political concerns, we must grasp the true emancipatory potential it has – and act accordingly. more